A World without Passports

According to my analytics dashboard, there’s a 70% chance you’re reading this on your phone. Maybe at home, or maybe while commuting to work, using your mobile data connection, for which you’ve probably signed up on a mobile contract. A contract for which you had to prove that you are you, likely by showing your national ID or passport. A contract for which you have to pay regularly, probably using a bank account that you also had to identify yourself for upon opening.

These days most things require some sort of identification, be it contracts, bank accounts, transit tickets or even just renting a zombie movie online. And for younger generations, this appears to be how the world works and always has been. You need a place to store your money? We need a copy of your passport. You want to be online? Show your ID. You want to buy booze or tobacco? ID, please.

But what if I told you that as little as one hundred years ago this wasn’t the norm but rather the exception? However, let’s not get ahead of ourselves and start at the very beginning.

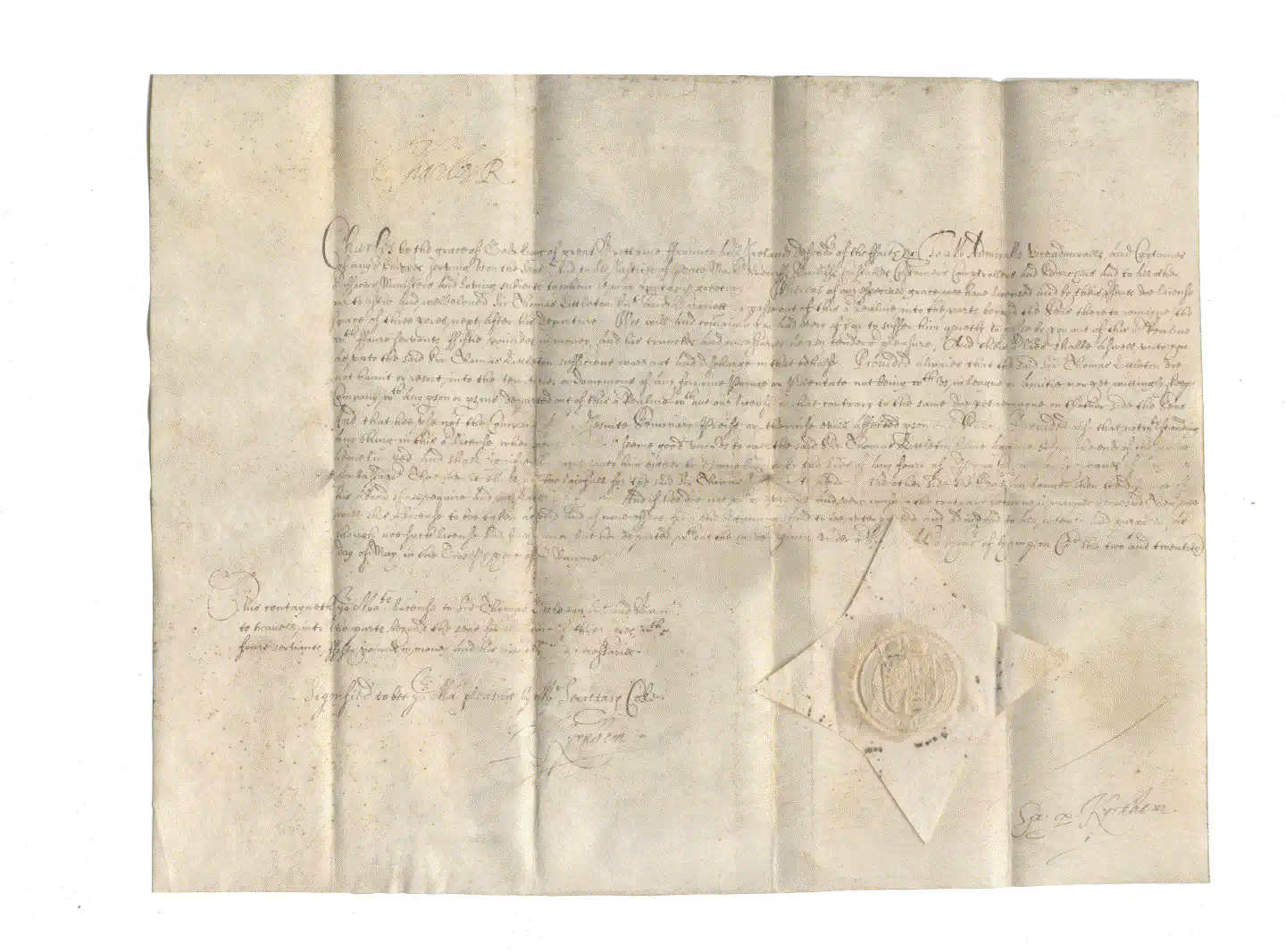

Back in 1414, King Henry V of England appears to have invented what some consider the first passport in Western society, as a means of helping his subjects prove who they were in foreign territory. The so-called Safe Conducts Act of 1414 introduced a document that was issued by the king (or one of the councils), basically telling others “Ye oughtest not to inflict harmeth on these fine men ‘r thou shouldst incur the wrath of his majesty.”.

Such passports however weren’t something that every citizen had to possess. On the contrary, they were a privilege afforded to important people only. Two hundred years later, in the 1600s and 1700s, today’s concept of passports and identity documents was still so foreign, that it wasn’t possible to accurately identify even the most infamous people in Western society.

Even though around 1855 the British government introduced what many call the first modern passport, up until the First World War, in 1914, the vast majority of people didn’t possess an identity document whatsoever. There wasn’t much of a need for them back at the time. And while for example birth certificates were issued in some countries like England since the 19th century, in the majority of places these documents did not exist until the 20th century. That’s also one of the reasons why, to this day, it’s possible to claim citizenship on many tropical islands by acting – and obviously looking – like someone who could have been born there in the mid to end 1900s, and by stating to have lost the birth certificate or not even having had one in first place.

In the industrialized western parts of the world, birth certificates weren’t much more than a piece of paper with some basic information and a stamp on it. Britain’s passport from 1855 appears to have been one of the first ones to not only contain a person’s name and a description but also a photograph. All on a single-sheet document that was nevertheless a valid identity document, e.g. for opening bank accounts – if the bank would even require identification at all.

Unlike for example China, where registration of residency was in place since the Han dynasty, and where it was used to control movement of people throughout the imperial territory, in the western hemispheres the widespread adoption of passports occurred only after World War I. And while there have been attempts to introduce passports throughout the West from as early as the 1700s, they weren’t successful and were abolished with the spread of intercontinental railways in the late 1800s. Governments simply weren’t able to deal with the ever-increasing amount of travelers, hence most Western countries more or less gave up on the efforts.

The First and Second World Wars changed all that. European nations instituted passport requirements, to be able to monitor and control people entering and exiting the countries, in an effort to deal with spies, dissidents, and others they deemed a threat to their power. Similarly, the US issued a passport requirement at the end of WWI in 1918, that was in place until the last day of the Wilson administration in 1921. The US made passports a requirement from 1941. With an amendment to the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, in 1978, it was deemed illegal to enter or exit the country without a passport – even in peacetime!

The modern passport as we know it today was created in response to the increasing need for a standardized document that could be used to verify a person’s identity and nationality for international travel. Modern passports were primarily introduced as a way to control immigration and improve security.

Similarly, the use of ID cards began to gain popularity during the 20th century, with governments around the world introducing them. The first identity card system was introduced in France in 1940, during the German occupation. The French government required all citizens to carry identity cards that contained personal information such as name, address, and occupation.

After the war, many countries continued to use identity cards for various purposes. In the UK, identity cards were introduced in 1952 to help control immigration and prevent welfare fraud. Other countries, such as Belgium and Italy, introduced identity cards as a way to combat terrorism. In the past decade, central and Western Europe have had amongst the strictest regulations in terms of identity checks. While you could simply travel across eastern European countries like Bulgaria and, let’s say, book Airbnbs without anyone caring, in Spain for example you were required to hand over a copy of your European ID or passport and have the renter submit it to the government, including the exact dates when you arrived and when you’ll be leaving. A look at Europol’s TE-SAT reports however shows that even though Spain, France, and the UK (not EU anymore) pursued some of the strictest and most privacy invasive paths in terms of identity checks, they have been and remain the countries with most terrorist activity across all of the EU. As shown in the 2016 trend report (page 11), activity between 2013 and 2015 even continued to grow.

FYI: Within the EU nations, citizens are allowed to travel using only their national IDs, requiring no passport to cross borders.

Over time not only national IDs but also passports evolved to include more information, such as the person’s place of birth and date of birth, which not only helped to make it more secure and difficult to forge but also made it easier to exactly identify people.

The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), a specialized agency of the United Nations, was established in 1944 to develop international standards for passport issuance and design. In 1981, the US became the first country to introduce machine-readable passports, and in 2006 the government started issuing biometric passports containing RFID chips. Similarly between 2004 and 2010 most European countries made the switch to biometric passports that have digital imaging and fingerprint scan information on their RFID chips.

Fun fact: During WWII, the Current Tax Payment Act of 1943 introduced tax withholding in the US for the first time. Similarly, it was only between 1952 and 2013 that EU member states introduced the EU withholding tax, a similarly sounding but different type of tax.

However, even though taxes themselves are as old and numerous as humanity, tax withholding, like identity, is a fairly novel concept and is in part made possible by the identity framework that was put in place for basically every financial transaction.

Biometric passports, also known as e-passports or digital passports, are travel documents that contain an embedded electronic chip (RFID) that stores personal information and biometric data such as fingerprints, facial recognition data, and iris scans. These days they are becoming increasingly common and are already used in many countries around the world. While biometric passports are seen as an improvement in passport security, they come with their own set of risks and concerns. Biometric data is incredibly personal and sensitive information that can be easily exploited if it falls into the wrong hands. One significant risk of these types of identity documents is cyber-security. As with any computerized system, biometric passport systems, too, are at risk of breaches, which could expose personal information and biometric data to malicious actors.

Biometric data can also lead to discrimination, particularly if the technology is not properly designed or implemented. For example, facial recognition technology is less accurate for people with darker skin tones, which could lead to discrimination against certain racial or ethnic groups. On the other hand, countries like China are prominent examples where biometric data is used specifically to target minority groups or people who cannot or refuse to provide identity or biometric data. India is another example where social services are tightly coupled with an individual’s digital identity and the lack of such will result in them being denied certain benefits.

Obviously, these risks seem worth taking for many governments as the advantages of being able to keep track of every single person and have them identifiable at any time seem to outweigh the individuals’ disadvantages. The use of biometric passports also allows governments to collect valuable data on individual citizens’ living patterns, as passports these days are no longer only used for crossing borders. While initially, governments were only able to track people’s cross-border movements, which could be used for immigration policies, monitoring national security threats, and emergency plans, these days passports are used throughout a variety of other areas, like banking and even online content. Thanks to identity documents like passports and national IDs, governments not only know where you travel to but also who you regularly call, what type of adult entertainment you enjoy, where your money is, and what you like to spend it on. Using multilateral agreements, states might even share this type of data across different agencies for “law enforcement”.

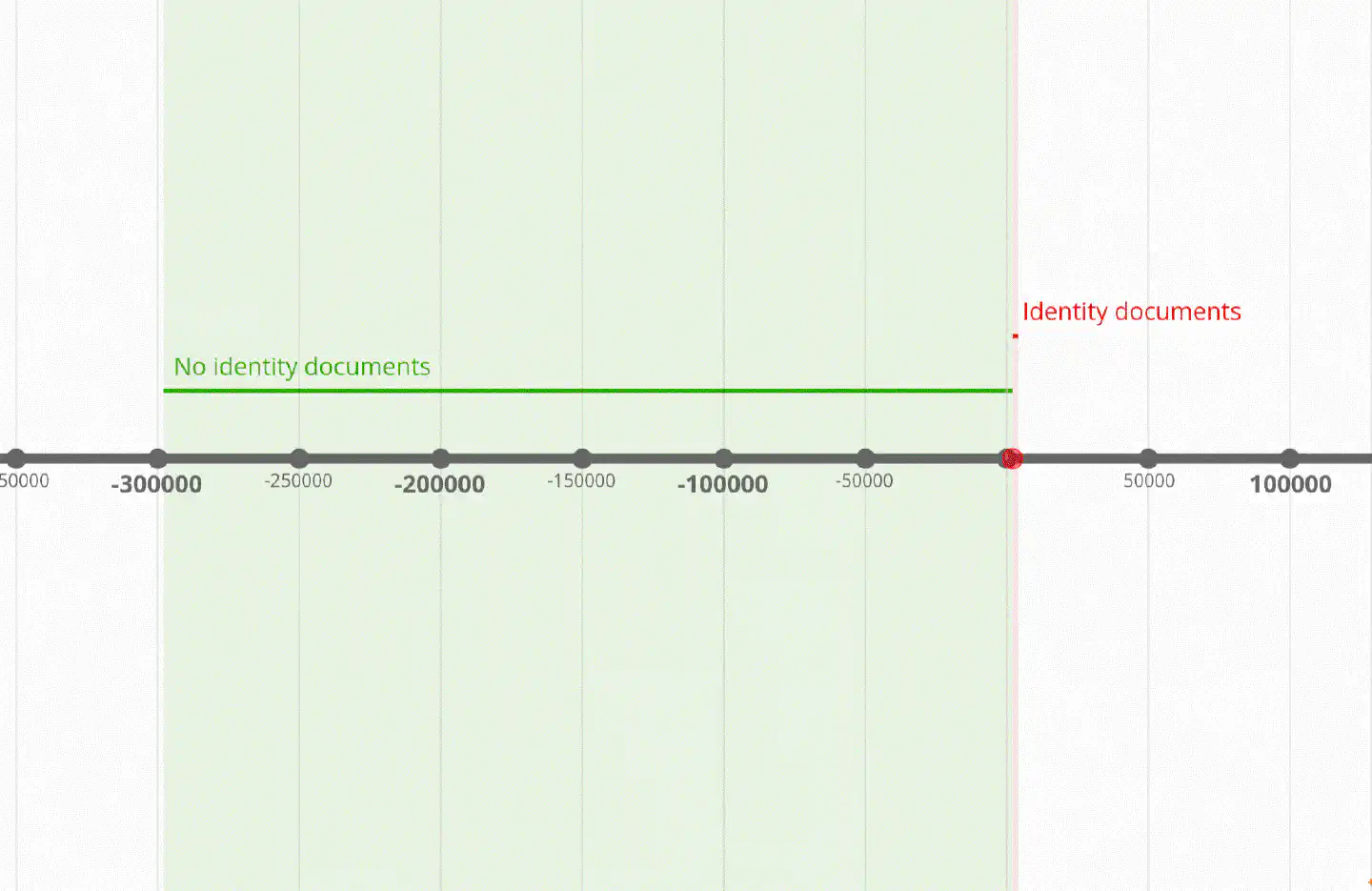

To put this in perspective, the modern Homo sapiens evolved around 300.000 years ago and has lived for roughly 299.900 without any need for identity documents whatsoever. It has only been in the last more or less 100 years that we seem to have collectively agreed, that in order to build a better world, whatever that might be, we need to make every human being universally identifiable – not only by assigning us identifiers, but also by storing fingerprints and other biometric data in searchable, interconnected databases. In addition, we have seemingly decided that it is necessary for society to only allow individuals to open bank accounts, sign up for mobile contracts, and watch horror movies if they agree to provide the respective service or seller with a document that contains many of our unique attributes. Today, even something as mundane as your e-mail provider or a social media platform might, in certain circumstances, ask for you to identify yourself using an identity document, to be able to continue using the service – a service that likely has been granted a deep look into your communication and your personal life already.

Not only do service providers get more information on us than they need: Governments can permanently link all data – that we generate by consuming these services – to us. For example, since ID checks are required for signing up on a mobile contract in many countries, governments could request providers to not only hand out information about a citizen’s communication metadata but also store and process important audio data, to allow them to use it for future identification purposes. Think Shazam but for voices. Our voices could then be used as yet another biometric attribute of the ID, without even requiring us to explicitly submit vocal data to the government. While facial recognition can still be obstructed by using masks, hats, and sunglasses, a person’s voice in daily interaction can usually not be fundamentally changed to make it harder to identify them. In addition, the service providers themselves can add this additional biometric information to their databases and even share it with other parties. Not to mention that such private data is regularly abused by those who gather it.

And as if the current state of ID documents and the privacy around them wouldn’t be bad enough already, when we take a peek into the future by adding other incentives like central bank digital currencies (CBDC), that are looming on the horizon, the outlook on privacy becomes very dire. Governments have long started to slowly outlaw paper currency and simultaneously push for digital transactions wherever possible. And people have been lured into handing over their data in return for the little convenience that debit cards and services like Apple Pay or Google Pay offer. And for the supposed benefits of sharing their shopping behavior with payback program companies.

With all digital financial transactions these days being ultimately linked to a person’s ID, it has become increasingly difficult to live off the grid. In fact, society has been conditioned so much into digital payments, that cash transactions these days have become a somewhat dubious thing to do, as anyone who ever tried to use cash for high-value purchases (jewelry, vehicles, real estate, etc), or even just pay in larger sums into a bank account will acknowledge. The moment you use the official, governement-issued currency in these days, you’re automatically being perceived – and often treated – as a drug dealer or worse.

However, Governments all across the world have long recognized the usefulness of linking IDs to financial transactions for more than just anti-money laundering and other measures against criminal activity. For example, Europe and its International Center for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD) have been working on a so-called “digital refugee card” for some time now:

According to the project description that we are now publishing, this card should not only be used for payment. The “usability of certain functions, such as payment transactions” should be limited to “certain geographies” and “deployment scenarios”. Authorities should therefore be able to ensure that asylum seekers can only shop in certain places. According to plans, the card can also be “extended to the effect that cardholder data can be called up directly with official/police terminals/equipment”.

The digital refugee card will serve as a replacement for traditional foreign registration cards, but it also integrates government-controlled payment functionality. Regardless of one’s stance on immigration, it should be clear that having a debit card that only works in places approved by the current administration is not only interfering with a person’s freedom but also sets a dangerous precedent for the future. If something like the digital refugee card becomes a reality, imagine who might be the next target group for a similar ID-and-payment card. No matter whether you were against or in favor of the “freedom convoy” protests in Canada, it showed how easy it is for a government to silence opinions by taking control of the finances backing them. In a world in which governments can simply freeze bank accounts at will, it is becoming more and more dangerous to have them equipped with even finer-grained controls over whose money and services get frozen and whose won’t, by forcing KYC upon every industry that is critical for surviving in today’s world: Banking, communications, travel, and many others.

While ID verification has certainly improved many aspects of doing business with one another, the institutions and individuals that today’s KYC-craze is supposed to target – terrorists, money launderers, corrupt businessmen and politicians, et. al. – are as unaffected by it as it gets. Meanwhile, it is the general public that is being given a hard time, with dozens and dozens of compliance requirements and restrictions. The powerful and well-connected can not only make millions disappear but also make themselves disappear – even with all the identity documents and KYC checks in place. However, it’s the average Joe that has to bear with the collateral effects that all these regulations have.

From today’s perspective, imagining a world without ID documents can be challenging though, as we have been conditioned into thinking that every interaction requires some form of verification of who we are, even though that’s not true in most cases.

To give a specific example, let’s have a look at telecommunication companies. In today’s world, signing up for a mobile contract will require you to hand over some sort of ID, even when it’s for example just a prepaid data-only plan. Clearly, there is no reason at all to provide a passport for identification, as it does not contribute to keeping society safe. Bad actors have various other means of obtaining anonymous internet access (think coffee shops) and will use techniques to anonymize their traffic and make them untraceable. Even though the carrier can link a specific connection to a passport, it won’t help with stopping online fraud or increasing cyber security. No reason at all is plausible enough for phone companies to require KYC, especially in the interconnected world of today, where connectivity has gained a similar status to electricity and other utilities. The only reasons to do so are nefarious surveillance capitalism business practices and privacy-infringing regulations from governments.

One might argue that KYC processes are an important tool to make sure that people are allowed to do business. However, even though implementing effective technological frameworks for keeping out bad actors is easier than ever before, it begs the question of whether access to certain services should be limited in the first place. Connectivity, as well as the financial system, have become the lifeblood of our world. Excluding individuals from either of these things will do more harm than good in the long run.

For other purposes modern solutions that do not hold on to individuals’ biometric data could be implemented. Instead of allowing the governments to process and store some of our most personal data (in the form of ID documents and passports), they could, for example, issue digital tokens that would certify access to individual services like social services or even residency. These tokens would not need to contain personal or even biometric data. Think of government-issued NFTs that can prove citizenship, residency, and access to government services anonymously. Such tokens could be issued for age verification (e.g. “Over-18” token, “Over-21” token), and they would be bound to a persons digital wallet, allowing individuals to prove that they’re over a certain age, that they are allowed to reside in a specific place and that they have access to social services.

A world without passports would require unprecedented levels of international cooperation and consensus among countries, which might be challenging to achieve. However, so will interconnected databases for passport- and biometric checks in the future.

Fun fact: Singapore has already started moving away from passport-based clearance to one that relies on pre-submitted data and facial scans. While this solution might eventually spare people from having their passports with them, it is still as privacy-invasive as the current passport-based immigration and will potentially only create a less privacy-respecting future in the long run.

Ultimately, we should be asking whether it makes sense to continue down the rabbit hole of personal identification, which seems to lead us to a rather dystopian future of humanity, or whether it would make sense to take a step back and reconsider the approach. The choice is ours and with one government-driven surveillance disaster after the other, it is probably about time to sit down and reconsider.

Sources & further information:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Identity_document

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Passport

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Machine-readable_passport

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biometric_passport

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Birth_certificate

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tax_withholding

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tax_withholding_in_the_United_States

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/European_Union_withholding_tax

- https://fxb.harvard.edu/2015/11/12/a-brief-history-of-national-id-cards/

- http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/magazine/8748441.stm

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/26566308

- https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2012/05/historical-echoes-our-checking-accounts-ourselves-or-say-good-night-gracies-checking-account/

- https://dial.global/good-dpi-more-than-tech-funding/

- https://www.biometricupdate.com/202310/fund-non-technical-parts-of-digital-public-infrastructure-for-best-results-dial

- https://www.thebanker.com/Michael-Wiegand-It-s-time-for-a-new-approach-to-financial-inclusion-1696231288

- https://ministers.pmc.gov.au/gallagher/2023/digital-id-and-ai-insights-how-albanese-government-leading-digital-evolution

- https://statescoop.com/fingerprints-face-scans-liquor-tobacco-new-york-biometric/

- https://washingtonstatestandard.com/2023/07/02/handprints-for-ids-state-liquor-board-discusses-biometrics-for-alcohol-sales/

- https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/our-common-agenda-policy-brief-gobal-digi-compact-en.pdf

- https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/08/digital-trust-how-to-unleash-the-trillion-dollar-opportunity-for-our-global-economy/

- https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/08/29/2023-18591/national-cybersecurity-center-of-excellence-nccoe-accelerate-adoption-of-digital-identities-on

- https://www.enisa.europa.eu/publications/digital-identity-standards

- https://www.gatesfoundation.org/ideas/articles/mosip-digital-id-systems

- https://www.zdnet.com/article/eu-votes-to-create-gigantic-biometrics-database/

- https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/politics/swiss-state-surveillance-on-the-rise/46472548

- https://edri.org/our-work/italy-introduces-a-moratorium-on-video-surveillance-systems-that-use-facial-recognition/

- https://decrypt.co/96188/european-union-proposes-crackdown-non-custodial-crypto-wallets

- https://hadea.ec.europa.eu/calls-proposals/equipping-backbone-networks-high-performance-and-secure-dns-resolution-infrastructures-works_en

- https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-news/revealed-uk-government-publicity-blitz-to-undermine-privacy-encryption-1285453

- https://politiken.dk/udland/art8587872/A-Democratic-Scandal-is-Unfolding-in-Denmark

- https://digit.site36.net/2022/02/21/plans-for-pruem-ii-eu-member-states-also-want-to-query-driving-licence-facial-images/

- https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-61550776

- https://www.patrick-breyer.de/en/eu-chat-control-bill-fundamental-rights-terrorism-against-trust-self-determination-and-security-on-the-internet/

- https://soylentnews.org/article.pl?sid=22/05/17/1337242&from=rss

- https://www.patrick-breyer.de/en/cybersecurity-eu-bans-anonymous-internet-sites/

- https://www.fairtrials.org/articles/news/french-court-rules-that-refusing-to-disclose-a-mobile-passcode-to-law-enforcement-is-a-criminal-offence/

- https://cryptobriefing.com/eu-moving-to-ban-privacy-coins-report/

- https://youtube.com/watch?v=QN65fbzhIz0

Cover photo by Henry Thong

Enjoyed this? Support me via Monero, Bitcoin or Ethereum! More info.